by Jake Mulligan

You can’t be blamed if you missed THIS IS NOT A FILM during its first trip through Boston theaters. Playing on a small screen at the Kendall Theatre for 7 days, the picture brought in miniscule grosses. No doubt, it had support – critics raved. I don’t normally put stock in this type of thing, but a 100% approval rating at RottenTomatoes.com is nothing to scoff at. Still, there’s something alarming on that Rotten Tomatoes page. Jafar Panahi’s effort is listed as a documentary. Go to Imdb.com, and you’ll see the same. Peruse the reviews – Andrew O’Hehir calls it a “video essay,” Christy Lemire, a “documentary,” A.O. Scott, a “masterpiece in a form that does not yet exist.”

The fact that THIS IS NOT A FILM is a stunning cinematic achievement seems to go without saying. I believe that it may be the best film I’ve seen thus far this year (irony notwithstanding,) and I’m surely not the only one. But what no one seems to agree on is what this 75-minute experience actually is. An essay? A documentary? A diary? Something else? All worthy interpretations, but they all reduce what Panahi has done. He’s made a narrative film, pure and simple; the exact thing the Iranian regime had suppressed him from making in the first place.

The big secret is, on the surface, this isn’t a grand political rebellion. It’s a simple story about a man, Panahi, trying whatever he can to transcend his house arrest – the Iranian government jailed him for years due to the color of a Beret he wore at a film festival in Montreal – to make a film. When we start, he’s bored; feeding his daughter’s iguana,  eating breakfast, making a call to a fellow director who’s been wanting to “film filmmakers when they aren’t making films.” Panahi is a passive subject – walking longingly past the cameras his family has set up, seemingly independent of his own interests.

eating breakfast, making a call to a fellow director who’s been wanting to “film filmmakers when they aren’t making films.” Panahi is a passive subject – walking longingly past the cameras his family has set up, seemingly independent of his own interests.

Eventually his partner shows up with a professional grade camera. Panahi shows clips and critiques his past films, all of which blur the lines between documenting reality and presenting narrative fiction. He shows videos of prospective sets and begins to act out the script of a film he failed to produce. He starts to walk around the house, filming his own plight (and the fireworks outside, celebrating the Persian New Year,) with an iPhone. None of it satisfies him. It’s only when co-director Mohjtaba Mirtamasb leaves, and Panahi fatefully picks up his camera to turn it on someone else, that he begins to find the beauty in the form again.

At first he’s talking about himself; questioning his ‘subject’ – a trash collector – about what he saw the night the police came to arrest him. By the end of the conversation, Panahi just wants to study the man himself. Once again, he’s  capturing daily life in Iran – as a director, and no longer a subject. And with the return to that artistic urge, the film (that is not a film) comes to an end. Forget the idea of a documentary. This is a soul-baring, autobiographical narrative film – an even more impressive prospect. This is the introspective cinema men like Jean-Luc Godard and Dziga Vertov dreamed of.

capturing daily life in Iran – as a director, and no longer a subject. And with the return to that artistic urge, the film (that is not a film) comes to an end. Forget the idea of a documentary. This is a soul-baring, autobiographical narrative film – an even more impressive prospect. This is the introspective cinema men like Jean-Luc Godard and Dziga Vertov dreamed of.

Because when you inspect the filmmaking itself, things get interesting. Certain scenes that cut back and forth between multiple perspectives (a cut from Panahi on his phone, to a shot of the iguana passing by, back to Panahi staring at the iguana, for example) would technically be impossible to capture ‘honestly,’ considering the amount of cameras (one) we know the team has. Most of the interactions with other characters occur offscreen; and could be easily dubbed. The garbage man Panahi speaks to at the conclusion just happens to be a University student with a vested interest in cinema, and he just happens to have also been at the apartment complex the same night Panahi was seized and arrested.

I can’t pretend to speak definitively, but all the evidence points to the fact that this is as scripted and pre-arranged as any of Panahi’s other films, if not more so (Mirtamasb has admitted, at the least, that this ‘day-in-the-life’ was filmed over more than a few days.) Yes, the craft suggests it, but that’s not all. The narrative progression is too tight, the subtext too intricate, for me to believe this is all off-the-cuff. No, it’s a masterful act of rebellion;  cinema as a stealth enterprise; a traditional narrative film by a man banned from making them; fiction that you’re tricked into accepting for reality.

cinema as a stealth enterprise; a traditional narrative film by a man banned from making them; fiction that you’re tricked into accepting for reality.

And as for the result, you can cut it up and analyze it one hundred different ways. Panahi, iPhone in hand, could be studying the nature of how picture quality and visual format dictates cinema. Perhaps he’s interested in whether his docu-drama will be accepted as truth or fiction. He could simply be trying to create a document of his life, from his overarching prison sentences, to his pets, down to the people he crosses path with in his apartment complex. He might even see NOT A FILM as a thematic re-telling of the script that got him investigated, which also (allegedly) focused on one girl locked indefinitely in her home; persecuted by a society that seeks to silence her. Hell, he might even just see the picture as just another work in his oeuvre; inquiring, as pictures like CIRCLE and OFFSIDE have, into the nature of Iranian society and the possibility of a humanistic cinema, and how the former tends to discourage the latter.

Or perhaps, he sees it as I do: as the definitive work of modern Iranian filmmaking, gleefully skirting the line between reality and art, between fiction and non-fiction, between what’s permissible and what will earn you a 20 year jail sentence. All of his countryman’s cinema bristles with the aftereffects of censorship and Orwellian working conditions. Here, the struggle between filmmaker and regime is not in the background, in the subtext, or relegated to academic studies of the film. It’s literally the narrative. It’s the text. It is his primary passion – the film is even dedicated to Iranian filmmakers; with blank spaces left in the special thanks column where their names should be.

Panahi doesn’t tell you how to think about Iran, and his place in it. He simply depicts it as it is, as he can afford to, without implicating anyone further. That is to say: from his apartment complex, and often speaking in a form of code (he may not complain about his situation directly, per se, but a prominently framed illegal DVD copy of the Ryan Reynolds feature BURIED articulates his situation well enough.) There’s a mysterious and ambiguous edge hanging over his actions, right up until the haunting final frames. THIS IS NOT A FILM? I disagree. This is a Film By Jafar Panahi, as much as any other. Not only that, it’s his masterpiece.

Panahi doesn’t tell you how to think about Iran, and his place in it. He simply depicts it as it is, as he can afford to, without implicating anyone further. That is to say: from his apartment complex, and often speaking in a form of code (he may not complain about his situation directly, per se, but a prominently framed illegal DVD copy of the Ryan Reynolds feature BURIED articulates his situation well enough.) There’s a mysterious and ambiguous edge hanging over his actions, right up until the haunting final frames. THIS IS NOT A FILM? I disagree. This is a Film By Jafar Panahi, as much as any other. Not only that, it’s his masterpiece.

THIS IS NOT A FILM plays tomorrow 11/30, and Sunday, 12/2, at 7PM. The Harvard Film Archive, 24 Quincy Street Cambridge, MA 02138. The HFA is playing the entirety of Panahi’s oeuvre over the weekend in their series JAFAR PANAHI: THIS IS NOT A RETROSPECTIVE.

And perhaps most importantly, there is the innumerable amount of modern filmmakers who count him among their influences – and none too subtly. And that list ranges from his spiritual son Quentin Tarantino to master filmmakers like Martin Scorsese to upstart youths like Edgar Wright (

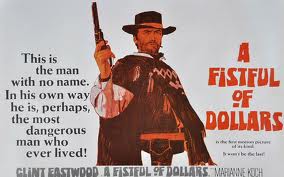

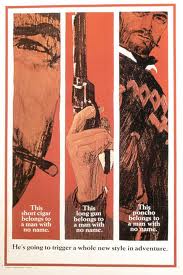

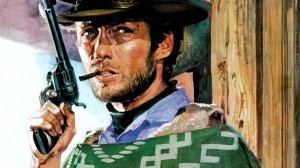

And perhaps most importantly, there is the innumerable amount of modern filmmakers who count him among their influences – and none too subtly. And that list ranges from his spiritual son Quentin Tarantino to master filmmakers like Martin Scorsese to upstart youths like Edgar Wright ( The sense of self-awareness that penetrates throughout all the operatic posturing, making every single second a joy to watch. The sense of deconstructing his chosen genre, the western, then building it back up with nothing more than it’s most essential moments – a hero emerges, a villain conquers, a gunfight – stretched out to unbearably tense lengths. And those beautiful, magnificent zooms – everything that we now know as simply Leone is present here. So, behind the “it’s a remake!” complaints is one of the greatest instances of a filmmaker finding the precise voice he would use to tell stories for the rest of his career.

The sense of self-awareness that penetrates throughout all the operatic posturing, making every single second a joy to watch. The sense of deconstructing his chosen genre, the western, then building it back up with nothing more than it’s most essential moments – a hero emerges, a villain conquers, a gunfight – stretched out to unbearably tense lengths. And those beautiful, magnificent zooms – everything that we now know as simply Leone is present here. So, behind the “it’s a remake!” complaints is one of the greatest instances of a filmmaker finding the precise voice he would use to tell stories for the rest of his career.